A series of norias on the Orontes River in Hama, Syria are based on ancient water-lifting devices improved by Al-Jazari and other medieval innovators. Photo © Milonk via Shutterstock.

A series of norias on the Orontes River in Hama, Syria are based on ancient water-lifting devices improved by Al-Jazari and other medieval innovators. Photo © Milonk via Shutterstock.

.

The classical age of Islamic civilization yielded advances in mechanical engineering along with mathematics and sciences.

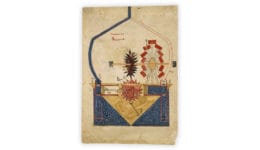

Although much of the technology developed in the Arab world between approximately 800 CE and 1250 CE was passed from masters to apprentices without being formally documented, a number of inventors compiled illustrated manuscripts to share their work and knowledge. The Banu Musa brothers, working in Baghdad in the ninth century, described approximately one hundred machines and automata in their Book of Ingenious Mechanical Devices (c. 850). They built upon Greek, Indian, and Chinese precedents, but added new innovations in the realm of automatic controls such as valves.

Several centuries later, the artisan-inventor known as Al-Jazari (1136–1206) demonstrated refinements and innovations in mechanical engineering through his numerous machines and automata, including five machines for raising water. Many of his creations, such as the famous elephant clock, served primarily as a source of amusement or wonder for his patrons, the Artuqid dynasty in Anatolia. However, the technology behind these devices was applicable to more utilitarian uses such as milling grain, pumping water, and automatically allocating water for irrigation.

Al-Jazari’s Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices (1206 CE) reflects a craftsman’s attention to the manufacture and assembly of mechanical components. He contributed to the improved efficiency of ancient water-lifting devices, the noria and saqiya — the former powered by flowing water and the latter powered by animals — by introducing the crankshaft and reducing intermittency. The noria, a large vertical wheel, releases water from a moving river to an aqueduct above. Traces of this legacy can be seen in the series of surviving norias in Hama, Syria, the oldest of which dates to 1361 and measures more than 20 meters in diameter. It was originally designed to furnish water to the city’s Grand Mosque, a hammam, and a residential quarter.

While Al-Jazari and other medieval Islamic craftsmen typically distinguished between useful and ornamental machines, the shared technological basis of these machines suggests the possibility of a synthesis of art and engineering. What inspires us today is the determination of these craftsmen and innovators to improve both the technical performance and visual presence of the devices they designed and built.