The transition from architectural school to the workforce can be jarring for many architects who aren’t trained to balance design aspirations with practical considerations.

By Mahmoud Abughazal, LEED AP. Head of Architecture and Interior Design

A typical architectural student spends five years or more learning how to create design concepts with the required skills that allow them to approach architectural design projects without limitations to their imagination. However, in practice, this knowledge must be balanced against realistic construction and collaboration principles.

Recentgraduates bring new ideas and new possibilities into an office, but they often have idealistic expectations about the role of a designer. In an interdisciplinary office like Omrania, good collaboration and communication skills are just as important as good design concepts. Despite what students may have learned in history class, no building springs fully formed from the mind of a single genius. It takes many people to create a successful building and it’s absolutely critical for young architects to learn how to work with other designers, as well as with structural engineers, MEP engineers, and the myriad other contractors and consultants needed to ensure that a building’s details reinforce its big ideas.

Omrania strives to create unified designs that reflect their cultural and architectural context. Our design principles include, but are certainly not limited to, culture, efficiency, flexibility, sustainability, legacy, and collaboration. While we greatly value these architectural ideals, the practical considerations of building, which are often unobserved by recent graduates, must be equally valued. Construction is not only the true test of a design, it is the true test of the designer.

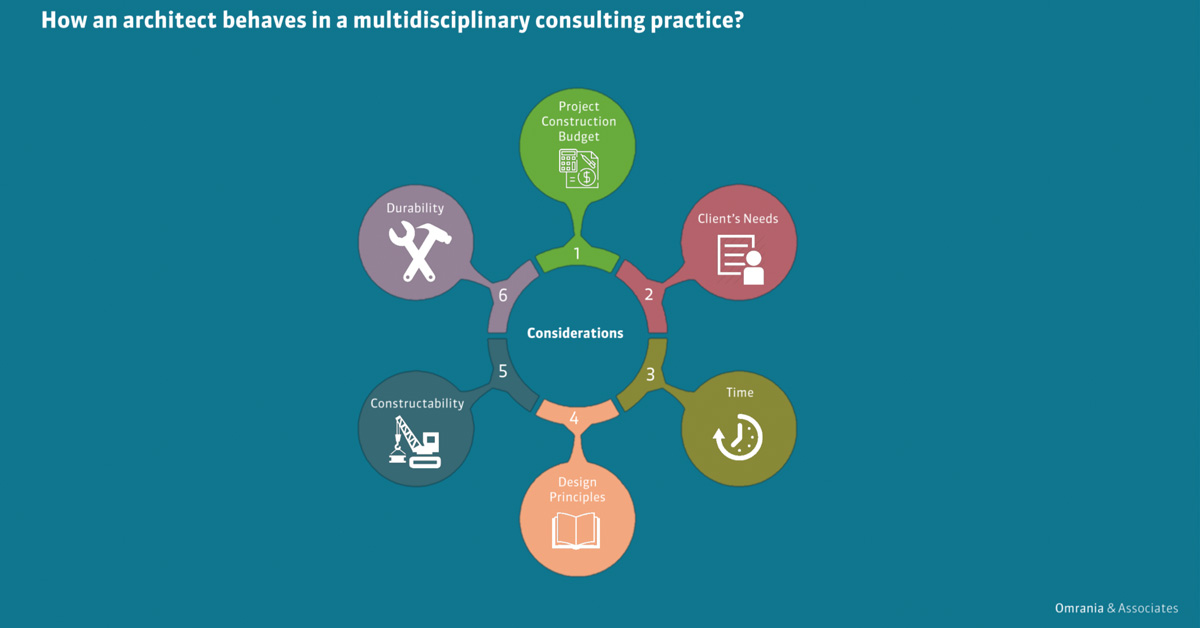

In addition to design principles, an architect’s priorities must include the project’s construction budget, the client’s needs, the project schedule, the constructability of the design and how it affects those first three priorities. Last but certainly not least, architects must consider a project’s durability — that is to say, how to create a “timeless building” that stands the test of time. How will it handle the pressures of the environment, and how will it be maintained? Can it adapt to changing programs or lifestyles? These ideas aren’t often taught at school, but must be quickly learned in professional practice.

Our work process reflects these complexities and is designed specifically to accommodate them. At Omrania, as at many other firms, our projects are divided into four primary phases: Concept Design, Schematic Design, Design Development, and the Final Design phase. Each phase begins with a meeting with all invested partners to discuss approach and strategy, but our Concept and Schematic Design phases are particularly noteworthy for the series of team charrettes, workshops, and internal presentations we conduct to ensure that all the parts of the design work in unison to meet the client’s needs. Again, good communication with project teams is very important. Coordination workshops continue through the later phases as we define the deliverables and specifications while also working to maintain quality and stay on budget.

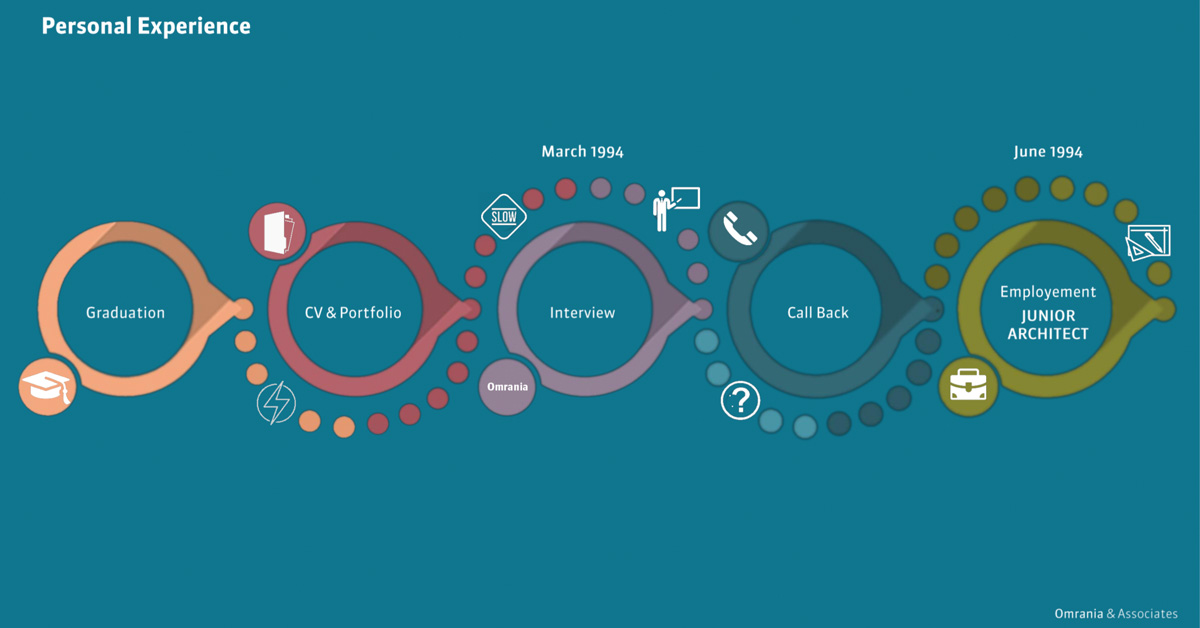

In many ways, the first job out of architecture school is a continuation of one’s education. As long as newly minted architects approach it with the same desire to grow and learn, they’ll find a rewarding professional career and few limitations to their imagination.

Mahmoud Abughazal is a member of Omrania’s Board of Directors.