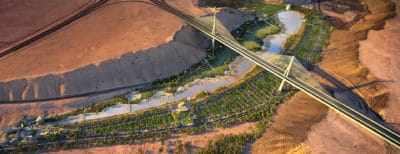

Prince Sattam Park, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. 3D Render © Omrania

Prince Sattam Park, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. 3D Render © Omrania .

In Riyadh, water is too precious to use only once. The secret to designing a public river promenade in a desert valley? High-tech water systems that recapture and treat municipal water for a variety of purposes—including creating a scenic recreational environment.

Prince Sattam Park is a passive-leisure landscape currently under construction on the city’s western outskirts. The park centers on a 1.5-kilometer river promenade within the Wadi Leban valley, an offshoot of the larger Wadi Hanifa, comprising 57 hectares in the valley bottom, plus 37 hectares at the top of the escarpment slopes. The valley parkland is traversed overhead by the majestic 763-meter-long, 167-meter-high Wadi Laban Bridge.

Our extensive engineering and design expertise was key to this technically sophisticated project. The hydrology of the natural watershed was overlaid with water-systems engineering to create a new, technologically mediated landscape that brings cultural and ecological functions together. The park design reflects the resource-conscious development and conservation strategy outlined in the Wadi Hanifah Comprehensive Development Programme (2010) by the Arriyadh Development Authority, the organization that is sponsoring the new park to serve Riyadh’s burgeoning population.

Prince Sattam Park, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. 3D Renders © Omrania

The key to the whole scheme, not surprisingly, is water — not just receiving it, but cleaning it and continuously recycling it through the park’s attractions and ecosystem. Prince Sattam Park’s water supply comes from the city’s post-consumer water-treatment plant. This “raw” water is purified through reverse osmosis and sterilized with ultraviolet light (and a separate stream with chlorine dioxide) before being released into the park’s signature water features: river, lake, and grotto. Further natural filtration comes from the “plant farm” along the site boundary fence.

Recalling the movement of a natural river, the water course rises from its hidden source, surrounded by mist and undergrowth, then flows down an increasingly large and verdant stream (with impermeable bottom), cascading over a series of falls and rapids, eventually reaching the placid lake at the bottom, home to the iconic Moon Balloon pier. The banks are designed to have a mixture of hard edging, beaches, rockery, planting, and vegetation, including tree to attract migratory birds. Pedestrian bridges provide vantage points to take in the view and create alternate circulation routes: children can play, racing homemade boats down the stream, while parents rest or picnic on the beaches or terraced areas that provide private havens along the riverbank. The high-flow recirculation system includes four intake pumps along the stream, plus a filtration/aeration device at the end of the lake, and pumps to recirculate the water via five concealed outlets upstream.

Prince Sattam Park thus represents an inventive and water-conserving approach to creating “new nature” in the modern city.