The Roman Forum, Ancient Rome, Italy.

The Roman Forum, Ancient Rome, Italy. .

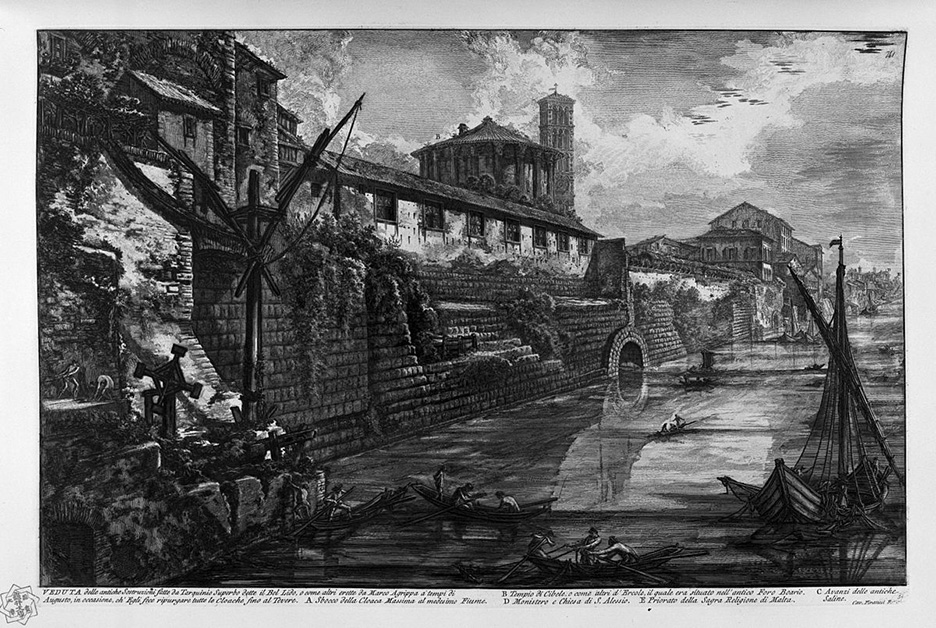

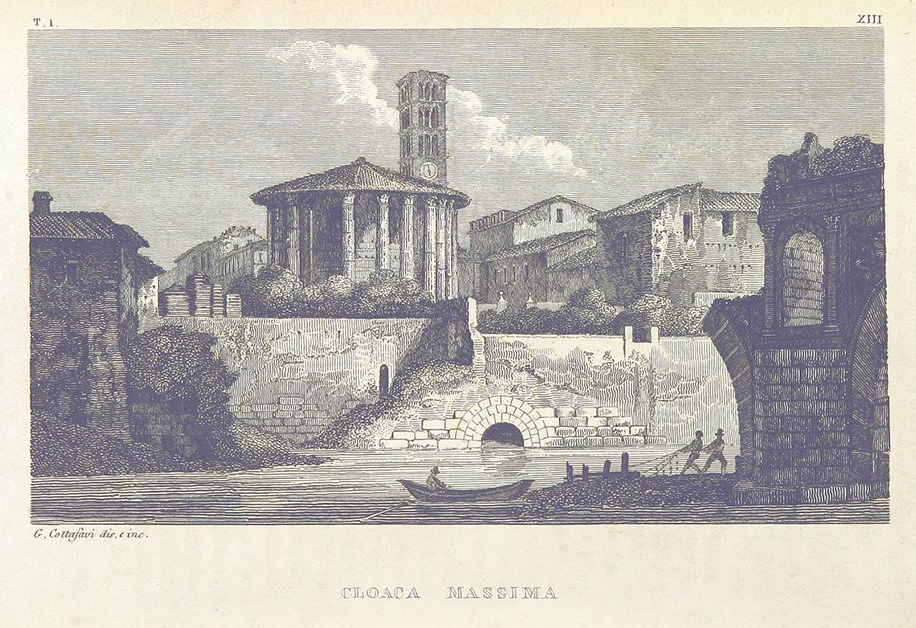

Constructed in Rome over two thousand years ago, the Cloaca Maxima (literally “greatest drain”) is one of the oldest large infrastructural projects in the Eternal City, predating its famed aqueducts and paved roads.

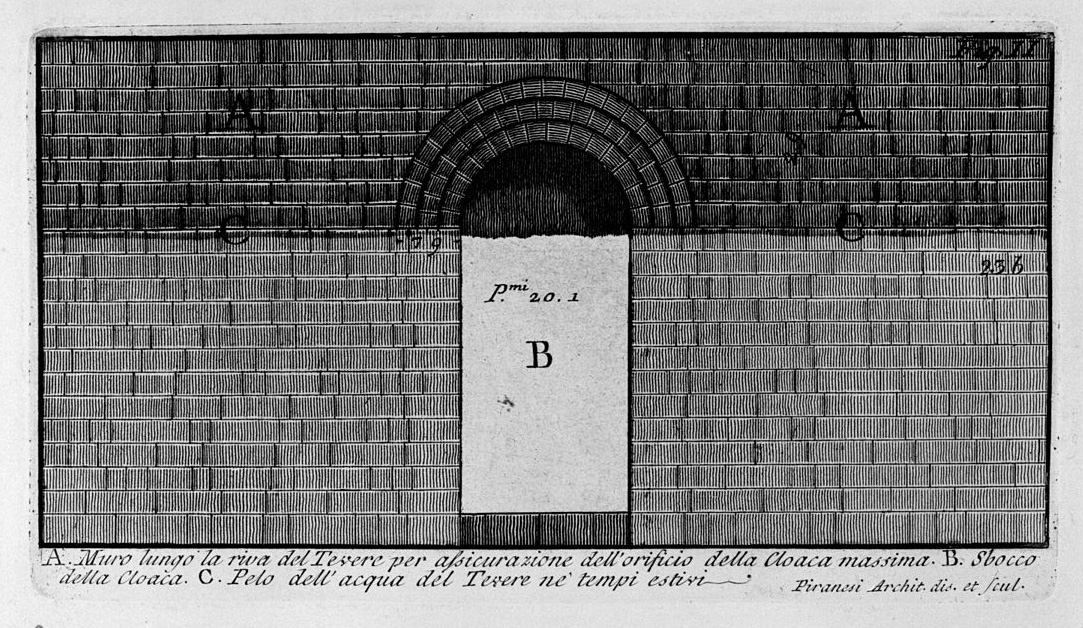

Built from massive blocks of volcanic rock and limestone, the monumental vaulted tunnel is large enough for a person to stand in. But it wasn’t always so grand. The Cloaca Maxima began as an open drainage canal following the path of an existing stream. Lined with stone to improve its efficiency, it brought water through the city’s central Forum and then out to the Tiber River. As Rome grew, so too did the canal, with shifts in direction corresponding to grand new civic buildings, and the addition of man-made channels leading from it. In the second century BCE, As sanitation and hygiene became more important for the city, the canal was covered to become Rome’s first true underground sewer system.

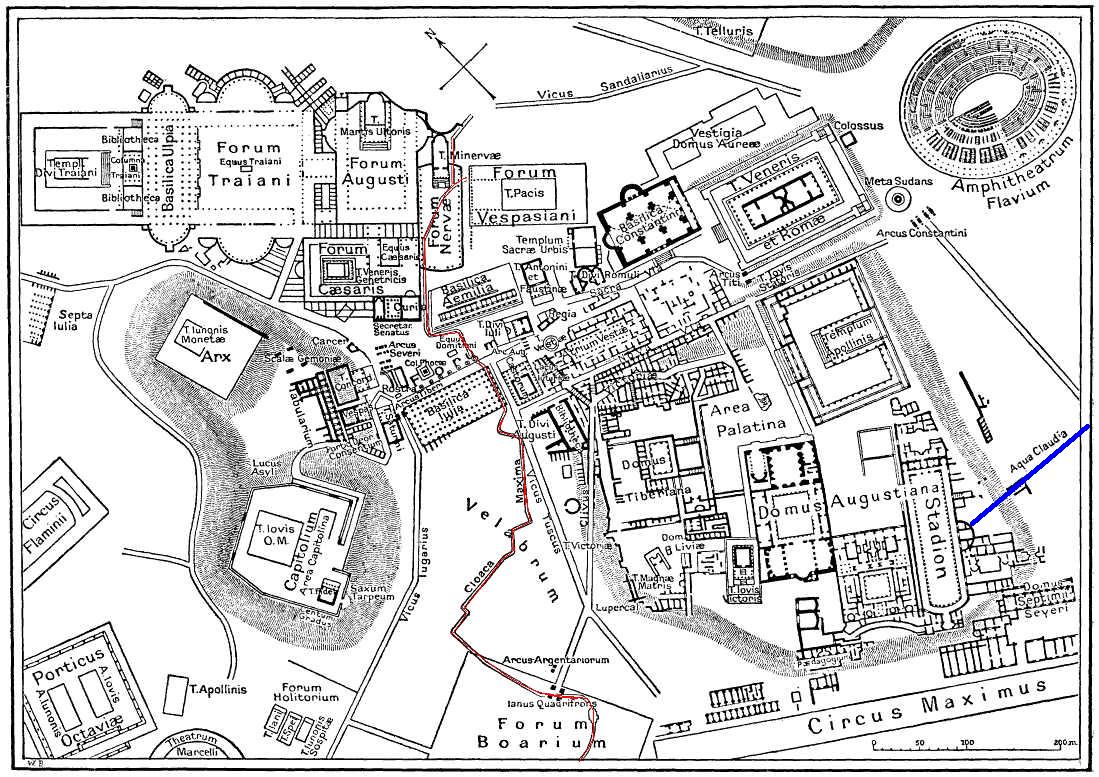

A map of central Rome during the time of the Roman Empire, showing the path of Cloaca Maxima in red.

The Cloaca Maxima was part of a sophisticated urban water system. In the first century CE, its entire length was traveled by Marcus Agrippa, a Roman statesman, soldier, architect, and the city’s first water commissioner. Agrippa oversaw the extension and improvement of Rome’s hydrology by adding new aqueducts, improving street cleaning, and expanding the sewer system. The new aqueducts were channeled into the sewer after supplying the public baths, fountains, and palaces. The constant supply of running water kept the sewers clean and unobstructed.

Unlike modern sewage systems, the primary purpose of the ancient Roman sewers was to carry away surface water. (Human waste was thrown into the street or carried away for farming). In fact, the sewer principally served the public areas of the city, providing little to no hygienic relief for crowded residential areas. Nonetheless, the system was a wonder and a matter of pride for Romans, and tours were sometimes given of the grand tunnels. In his grand book Natural History (79 CE), Pliny the Elder writes of the sewer:

“In the streets above, massive blocks of stone are dragged along, and yet the tunnels do not cave. They are pounded by falling buildings…The ground is shaken by earth tremors; but in spite of all, for 700 years from the time of Tarquinius Priscus, the channels have remained well-nigh impregnable.”

Hundreds of years later, Lewis Mumford, in The City in History (1961), expresses similar wonderment at the tunnels’ durability and its value. “With its record of continuous service for more than twenty-five hundred years, that [sewer] structure proves that in the planning of cities low first costs do not necessarily denote economy… on these terms, the Cloaca Maxima has turned out to be one of the cheapest pieces of engineering on record.”

It is worth noting that the Romans were not the first civilization to build underground sewers: the Egyptians had already pioneered the use of vaulted underground drains. And today, only a trickle of runoff water flows through what is left of the Cloaca Maxima. Still we marvel at this monumental undertaking, at once an architectural and engineering accomplishment and a demonstration of visionary political leadership.