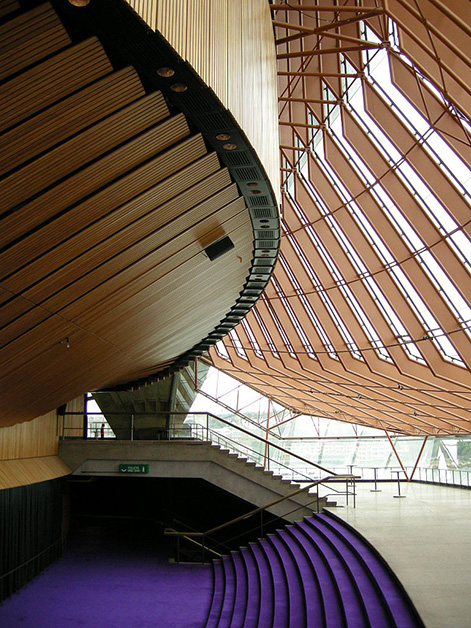

Sydney Opera House (1973) . Photo © DuncanSharrocks

Sydney Opera House (1973) . Photo © DuncanSharrocks

Never one to imitate or repeat himself, Utzon’s designs are all rooted in the traditions of the places he worked. He drew inspiration from everything he saw and experienced, from the Mayan pyramids in Mexico to the design of a tea house in Japan.

Today, when we see the Sydney Opera House, it is no less inspiring a vision than when it was completed in 1973. Designed by Danish architect Jørn Oberg Utzon (1918–2008), its sailing forms can perhaps be traced to Utzon’s childhood in Denmark, where he grew up as the son of a naval architect and spent his childhood fascinated by ships and by art. After the design was selected out of 233 competing proposals in 1957, Utzon and the engineer Arup had to figure out how to build the sculptural concrete shells of the roof. With the “Spherical Solution ,” discovered in 1961, they derived the soaring roof forms from the surface of a sphere.

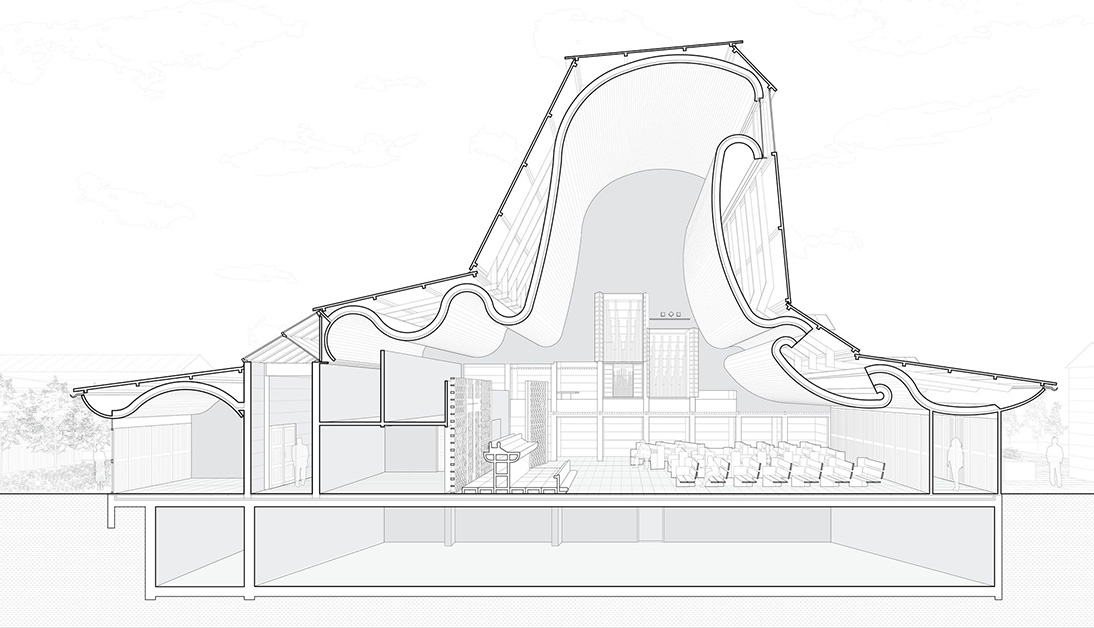

Though Utzon designed buildings around the world, no landscape inspired him more than his native Denmark, where he was most prolific. In the outskirts of Copenhagen, the understated form of Bagsvaerd Church (1976) conceals an inner sanctuary defined by a curving concrete ceiling that casts a soft light reminiscent of the clouds that inspired it. Despite the bold forms, there was always a human element to his work. The Fredensborg Housing Estate (1962), one of two courtyard-style housing developments he competed in Denmark, was inspired by Chinese and Turkish precedents but shaped by the local landscape. He helped select the site and planned the 77-home development to maximize individual privacy while ensuring every home had access to natural light and views of the surrounding countryside. Utzon’s housing projects were specifically cited by the jury of the Prizker Prize, which he was awarded in 2003, for being “designed with people in mind.”

Utzon built several homes for himself and his family, including the villa Can Lis in Mallorca, Spain. Built in 1973 using local materials, including a pink sandstone, the house is a quiet retreat, at once bold and understated, that reflects its surrounding landscape.

Utzon’s work can be difficult to classify and doesn’t fit easily into the grand historical narrative of Modernism. The National Assembly Building in Kuwait (1983), for example, draws from an array of Middle Eastern influences, with integrated ornamentation inspired by indigenous plants and Islamic patterns. But the dominant form is the massive public square, enclosed by thin piers supporting a swooping concrete roof whose billowing underside recalls the interior of a Bedouin tent. As he did with the Sydney Opera house, Utzon made a massive concrete form feel almost weightless. The structure, damaged during the first Gulf War, was rebuilt in 1993.

Utzon’s buildings have always been defined by their place and purpose, while still feeling ahead of their time. Perhaps that’s why his work still resonates today. As noted architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable noted in her Pritzker jury comments, each Utzon project “displays a continuing development of ideas both subtle and bold, true to the teaching of early pioneers of a ‘new’ architecture, but that cohere in a prescient way…to push the boundaries of architecture toward the present.”