View of the Parc de la Villette in Paris, France, designed by Bernard Tschumi. Photo © William Beaucardet

View of the Parc de la Villette in Paris, France, designed by Bernard Tschumi. Photo © William Beaucardet

The Parc de la Villette in Paris, France, dramatically expanded ideas of what an urban park could be. The 1982 competition to design the park, won by the Swiss architect Bernard Tschumi, attracted more than 450 proposals from around the world seeking to envision “a park for the twenty-first century.”

Built on the site of a former slaughterhouse, La Villette was designed to be a continuation, rather than a rejection, of the city. According to Tschumi the park can be understood as “one of the largest buildings ever constructed — a discontinuous building but a single structure nevertheless.” Thus La Villette, which was opened over a span of 11 years beginning in 1987, is conceived as a “social and cultural park” rather than an image of nature or a “simple landscape replica,” as Tschumi disparaged the nineteenth-century designs of Frederick Law Olmsted.

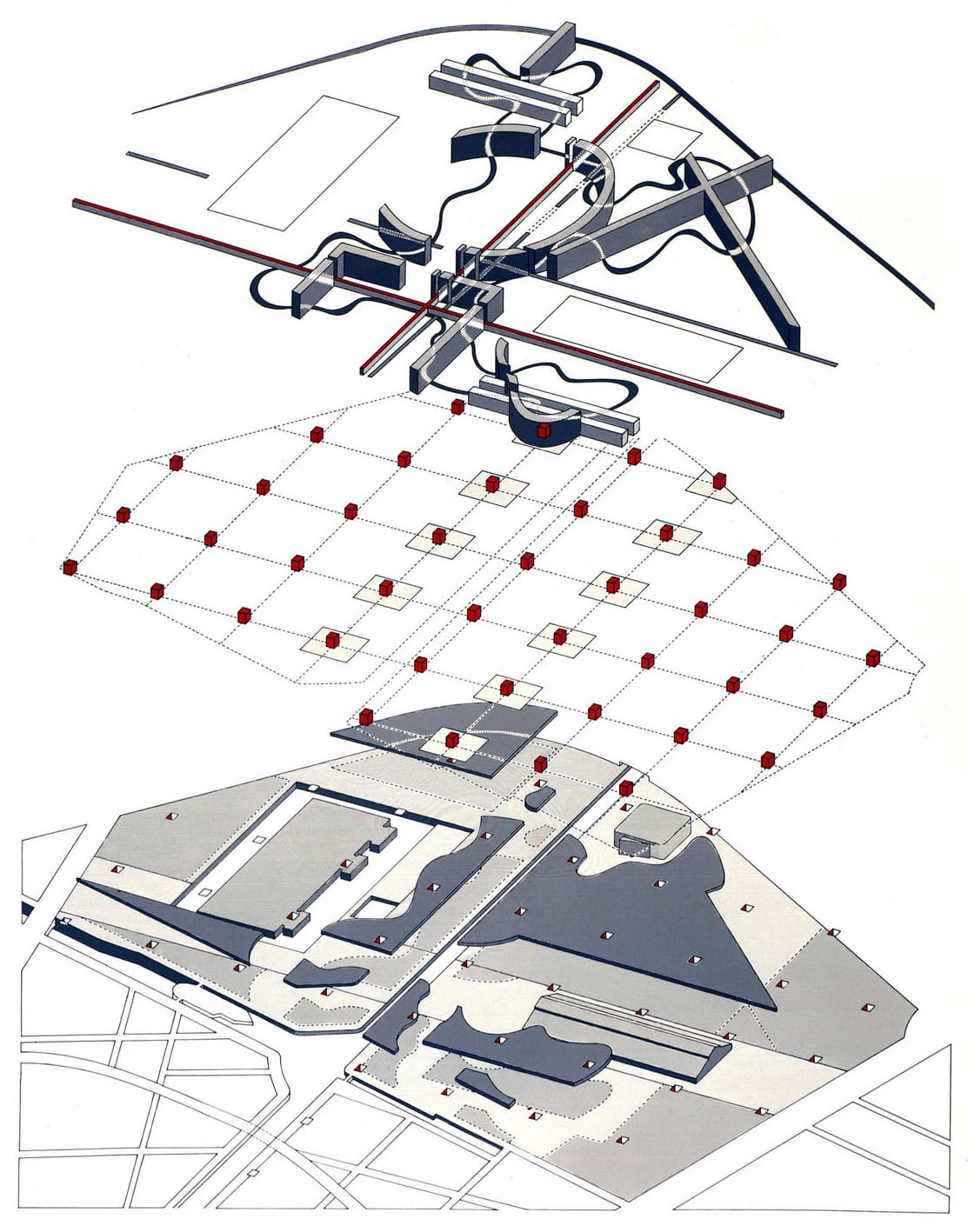

Superimposed systems of surfaces, points, and lines in the design of the Parc de la Villette. Image © Bernard Tschumi

Tschumi attempted to create an urban density of activities through the superimposition of three organizational principles: points, lines, and surfaces. The points comprise a series of bright red architectural “follies” arrayed across the park’s 55 hectares on a 120-meter-square grid. These small buildings, each a different permutation of an exploded 10-meter cube, house the wide variety of programs (workshops, restroom facilities, cafés, galleries, etc.) that were prescribed by the competition brief. The lines comprise systems of movement while the surfaces are the landscaped gardens — designed by a number of landscape architects, including Alexandre Chemetoff — which are scattered around the site.” The collisions and “disjunctions” created by the coming together of all these spaces are meant to encourage visitors to determine their own ways of using the park.

As one of President Francois Mitterand’s famed “grands projets,” the Parc de la Villette was intended to place Paris at the forefront of contemporary architecture and urbanism. Charles Waldheim, a professor at Harvard University, considers the park a forerunner to landscape urbanism, stating: “La Villette began a trajectory… in which landscape was itself conceived as a complex medium capable of articulating relations between urban infrastructure, public events, and indeterminate urban futures for large post-industrial sites.”

In this regard, the park has catalyzed a new generation of urban parks in the last three decades.