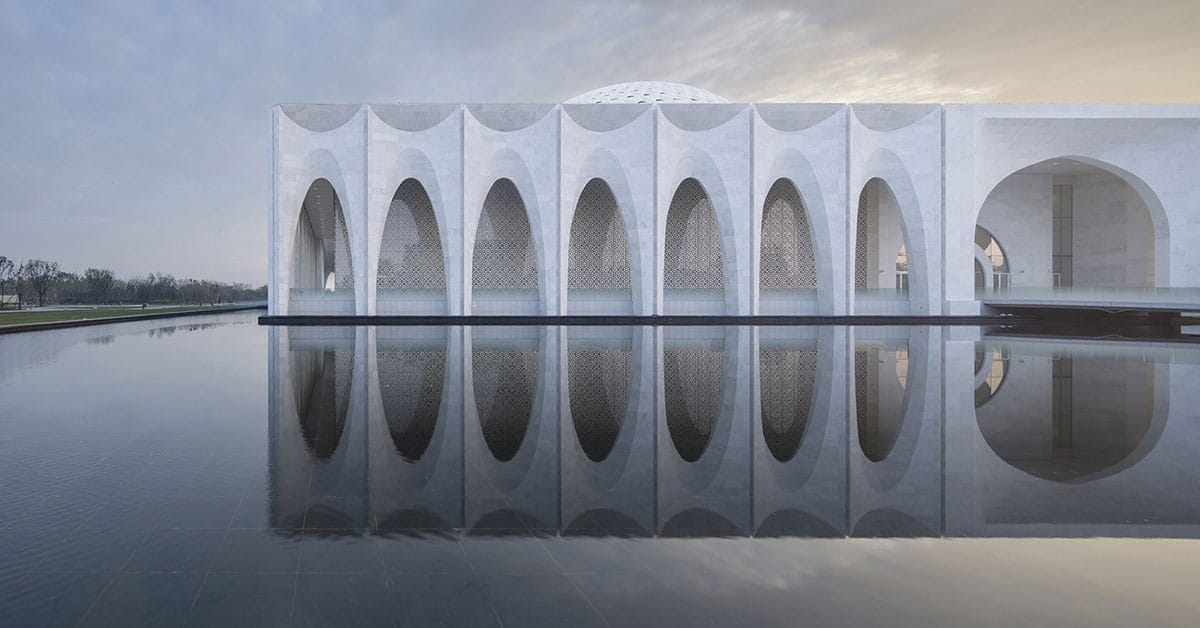

KAFD Grand Mosque, Riyadh. Omrania, 2017. Photo © Tamara Hamad / Omrania.

KAFD Grand Mosque, Riyadh. Omrania, 2017. Photo © Tamara Hamad / Omrania.

The design of new mosques poses considerable challenges to contemporary architects, who must honor the past while leaving room for continuing evolution of a living building type.

By: Nihad Alamiri, Marketing Manager – August 2017

Today, most architects stand in awe before the grand edifices that were built in the past. The dome of the Selimiye Mosque (1574 CE), in Edirne, Turkey, constructed by the great architect Sinan, covers a span of over 50 meters without a single bit of concrete. Such mosques represent a major source of inspiration for modern architects, but also a huge challenge for those who attempt to follow in their footsteps.

Modern architects tend to approach the challenge of mosque architecture in three ways. The first method is to reproduce, more or less faithfully, the forms and ornament of respected buildings from the past. For example, the Khatem al-Anbiyaa Mosque (2005) in downtown Beirut evokes Ottoman precedents with its central dome and four tapering corner minarets. The Siddiqa Fatima Zahra Mosque (2011) in Kuwait loosely recalls the form of the Taj Mahal. A more contextual, less literal version of this approach can be seen in the Imam Turki Bin Abdullah Grand Mosque of Riyadh (1992), where architect Rasem Badran “recreated and transformed the spatial character of the local Najdi architectural idiom without directly copying it,” in the words of the Aga Khan Award statement.

A second, more eclectic design approach for new mosques consists of mixing and matching historic styles. Practitioners of this method aim to consecrate in one building the wealth of traditions and architectural styles that have emerged throughout the history of Islam. The quintessential example of this eclectic approach is Abu Dhabi’s Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque (2007), whose design by Yousef Abdelky combines classical Mughal layout and dome design with Moorish-style archways, Arab-style minarets, and other pan-Islamic elements.

The third approach to mosque design today, still less common than the others, is to create fresh, new architectural forms to accommodate the time-honored religious and social functions of the mosque. With this more creatively open approach, architects embrace the expressive potential of contemporary building technologies, just as their predecessors pushed the limits of masonry construction and tile mosaics. Omrania sought inspiration in the crystalline geometries of “desert rose” sand crystals in designing the central mosque for the new King Abdullah Financial District (KAFD) in Riyadh — recently shortlisted for a 2017 World Architecture Festival award — with steeply raked elevations fusing into a dome of faceted plates.

Other recently completed contemporary mosques demonstrate the flexibility of the essential mosque typology, which ultimately is defined only by a space for prayer and a clear orientation toward Mecca. Both the North Mosque in the Bahrain Bay Development (Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, 2010) and the KAPSARC Mosque in Riyadh (HOK, 2014) have monumental cube-shaped central spaces whose geometric simplicity contrasts with the complexity of ornament and details. The North Mosque, clad in stone, has triangular windows in an offset pattern; while the KAPSARC Mosque, clad partially in glass, is adorned with highly intricate motifs on the exterior and interior. In Dubai, the Abdul Rahman Siddique Mosque by (Yaghmour Architects, 2009) combines unadorned stone volumes with patterned glass screens, a translucent dome, and a asymmetrical stone-and-glass minaret. L.E.FT Architects took on the challenge of converting an existing masonry structure in Moukhtara, Lebanon into a jewel box of a mosque, the 100-square-meter Amir Shakib Arslan Mosque (2016), by adding a secondary envelope of thin white-painted steel plates aligned in the direction of Mecca.

Istanbul in recent years has received several architecturally interesting mosques, some of which engage the Ottoman tradition and some of which take a new direction entirely. The central space of the Yesilvadi Mosque (Adnan Kazmaoğlu Mimarlık Araştırma Merkezi, 2004) in the Ümraniye district is covered by two half-domes of different diameters, allowing natural light to pour in through the hemispherical opening along the concrete shell. Downplaying the question of form altogether, the subtly constructed Sancaklar Mosque (Emre Arolat Architects, 2012) is carved into a terraced hillside on the rural outskirts of Istanbul, emphasizing the role of landscape and filtered light in shaping the religious experience.

Smaller and humbler mosques can be just as architecturally challenging — and rewarding — as the larger ones. For example, the 750-square-meter Bait Ur Rouf Mosque in Dhaka, Bangladesh (Marina Tabassum, 2012), built of brick using traditional methods, choreographs an exquisite play of light within. The plinth on which the mosque stands not only accommodates the 13-degree rotation of the square structure on axis with Mecca but also creates a vibrant public space for the community, raised above the flood line. Elsewhere in Bangladesh, in the port of Chittagong, the minimalist Chandgaon Mosque (Kashef Mahboob Chowdhury, 2007) consists of two low-slung monolithic volumes with wide openings carved into their solid masonry walls, visually and physically bringing the landscape inside the court. A split dome and skylight form a circular aperture above the prayer hall.

Architecturally ambitious mosques are springing up in regions outside the Middle East as well. The central mosque of Cologne, Germany (Paul Böhm, 2017) makes expressive use of reinforced concrete shell construction, as does the Islamic Center of Rijeka, Croatia (2013), based on designs by sculptor Dusan Dzamonja. In Singapore, the Assyafaah Mosque (Forum Architects / Tan Kok Hiang) poses an alternative to the Middle Eastern model while making extensive use of recognizably Islamic arabesque patterns on aluminum screens and tilework. The majestic Da Chang Muslim Cultural Center (Architectural Design & Research Institute of SCUT, 2015), while not a mosque, contributes to this architectural lineage with its uniquely modern take on the arcade, skylit dome, and geometric patterns.

Even the most boldly original contemporary mosques take up many of the traditional preoccupations of mosque design — the unifying aspect of the prayer hall, the treatment of light and shadow, the focused use of ornament and color to signal a kind of spiritual oasis. The challenge is to address these timeless aspects in a contemporary aesthetic idiom.

Architects will continue to research and argue over the different approaches to the design of mosques. But such debates ultimately reflect the openness of Islamic culture and religious practice to a multitude of architectural interpretations. The long and rich history of mosque design shows that Muslims have long been able to accommodate innovation and differences to reflect their diverse cultural expressions throughout a Muslim Ummah — a community of more than a billion adherents thriving in widely varying societies around the world.

This post is the third in a series on the architecture of mosques. The previous two explored the historic evolution of mosque architecture and the challenges involved in the preservation of historic mosques.