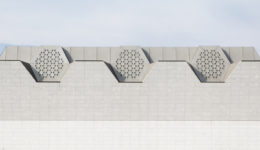

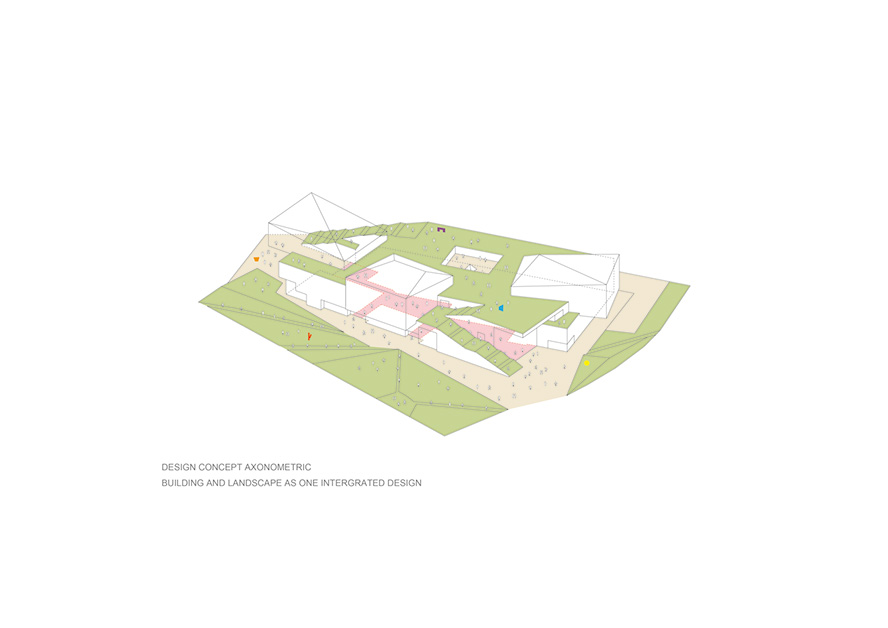

Aga Khan Museum, Toronto. Maki and Associates with Moriyama & Teshima Architects, 2014. Photo © AKDN / Janet Kimber

Aga Khan Museum, Toronto. Maki and Associates with Moriyama & Teshima Architects, 2014. Photo © AKDN / Janet Kimber .

The esteemed Japanese architect continues to produce warmly modern buildings that blur influences from the East and West. His thoroughly modern design sensibility is tempered by a regard for the human scale, as seen in the traditional architecture of his home country.

Fumihiko Maki was born in Tokyo in 1938. He experienced the vast reconstruction of his city after World War II as an “almost surrealistic transformation” that had a profound impact on his work. As he recalled in his 1993 Pritzker Prize acceptance speech, the Tokyo of his early childhood was almost like a garden-city, where buildings were “low in scale and subdued in color and texture” with “clay-tile roofs and wooden finishes.” It was also an era that marked the emergence of modernism in Japan. Some of Maki’s earliest memories of architecture involved the “articulated cubic forms” and “floating interior spaces” of modernist park structures.

In the 1960s Maki became associated with a group of young Japanese architects known as the Metabolists, who were inspired by economic theories and biological processes of growth. Maki embraced the reality of a constantly changing city, but unlike some of his fellow Metabolists, he looked to build upon historic forms and ideas. His attention to the human scale is seen in his Hillside Terrace Apartments, a collection of structures built in seven phases between 1967 and 1992. The residential complex is inspired by traditional Japanese neighborhoods like the one Maki grew up in. It uses transparency, layering, and changes in elevation to create spaces that feel open despite the project’s overall density.

The Fujisawa Gymnasium (1984) marked a turning point in his career toward more complex spaces and forms. The building’s soaring curved roof seems to hover over its expansive column-free interior. Maki has described the project has evoking both Gothic architecture and early Modernism — two very different styles that are nonetheless both known for creating a sense of lightness.

The Tokyo arts center known as Spiral (1985) is one of Maki’s most recognizable works. Its exterior weaves together disparate elements that reflect both the eclectic Aoyama neighborhood and the building’s complex multi-use program. Inside, the exhibition spaces, cafe, and theater are linked together through a continuous spiral ramp that gives the building its name.

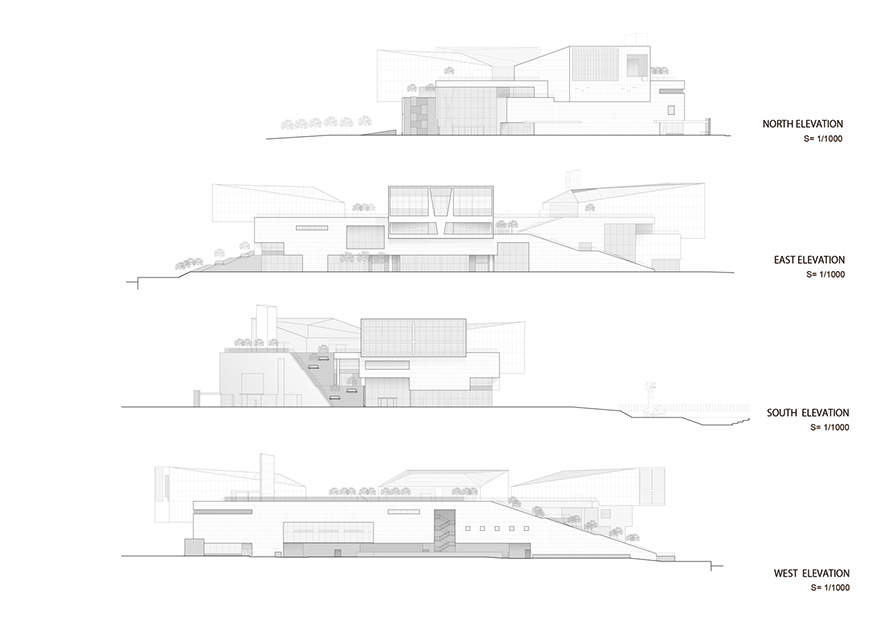

The Aga Khan Museum in Toronto (2014) is Maki at his most restrained and his most poetic. The white granite building wraps a courtyard whose patterned glazing casts intricate arabesque patterns across the interior spaces. Maki calls it “a celebration of light and the mysteries of its various qualities and effects.”

Maki has left his mark around the world in the form of sophisticated buildings in urban environments, from the National Museum of Modern Art in Kyoto (1986) to the MIT Media Lab in Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA (2009) to Nagano City Hall (2016). What elevates all these projects above the ordinary is an understanding of the host city, of construction methods and materials, and of the occupants’ way of life.

“Architecture can no longer provide the old order of traditional townscapes,” Maki has said, “but it may have an even greater influence today as the nexus between human beings and a constantly changing environment.”