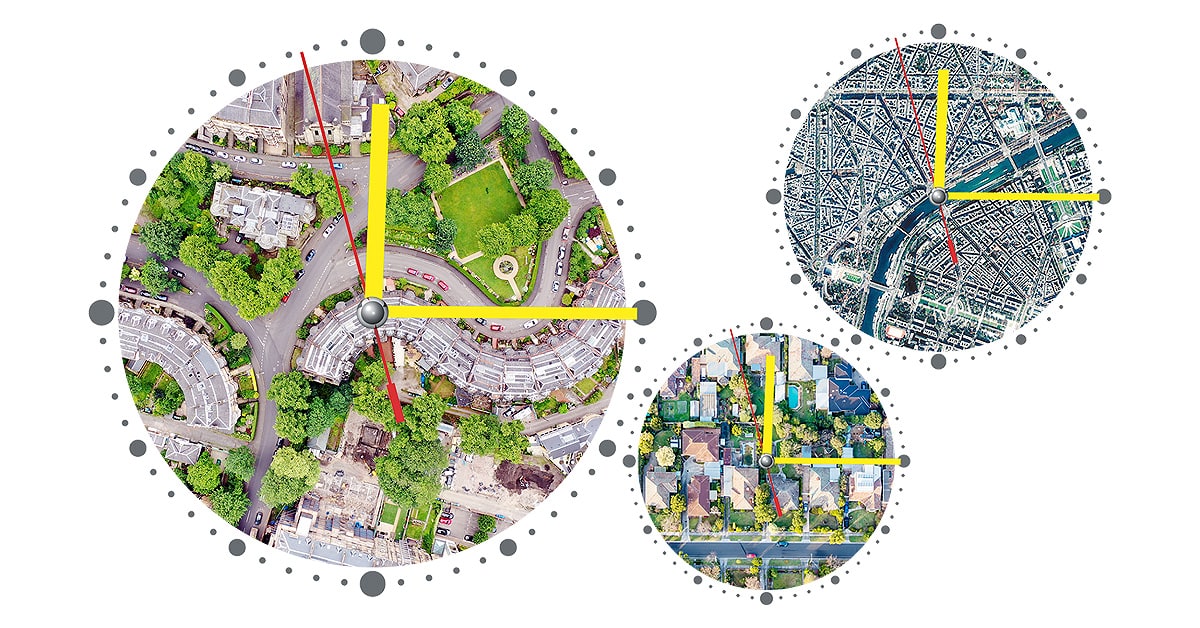

Aerial views of Glasgow, Paris and Melbourne. Photo © Shutterstock; Getty.

Aerial views of Glasgow, Paris and Melbourne. Photo © Shutterstock; Getty.

The idea that city residents should have access to daily necessities within a 15-minute walk recalls ancient cities in the Middle East and beyond. Today, planners are seeking to combine walkable and bike-friendly neighborhoods with high-tech forms of urban mobility. The result could be more sustainable, livable, and contextually appropriate cities.

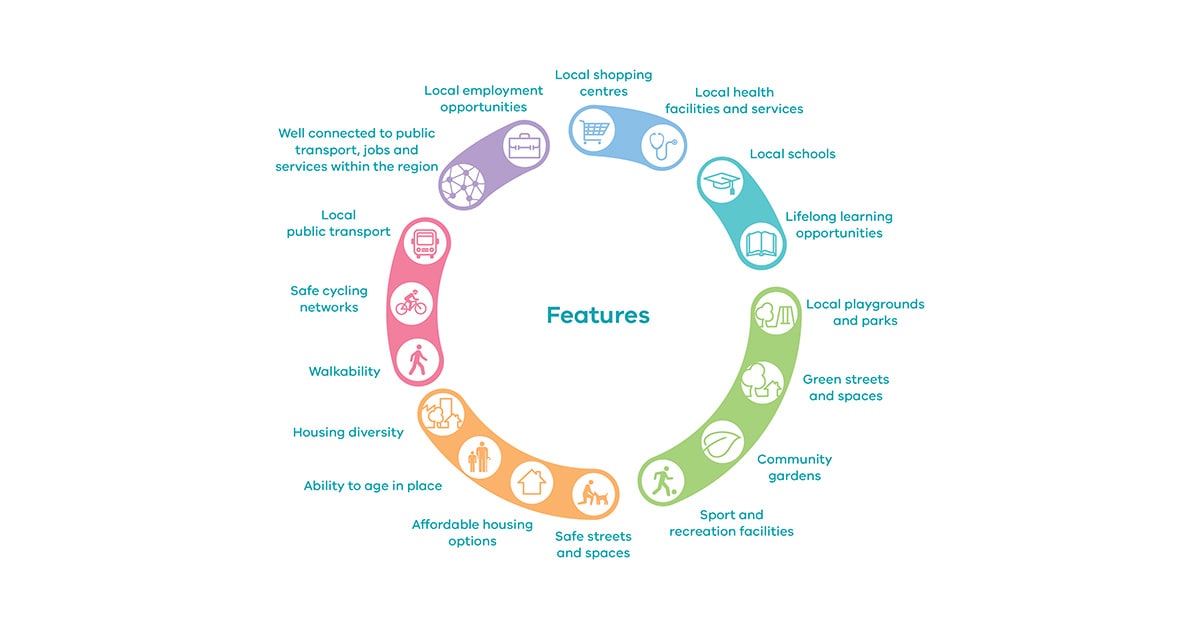

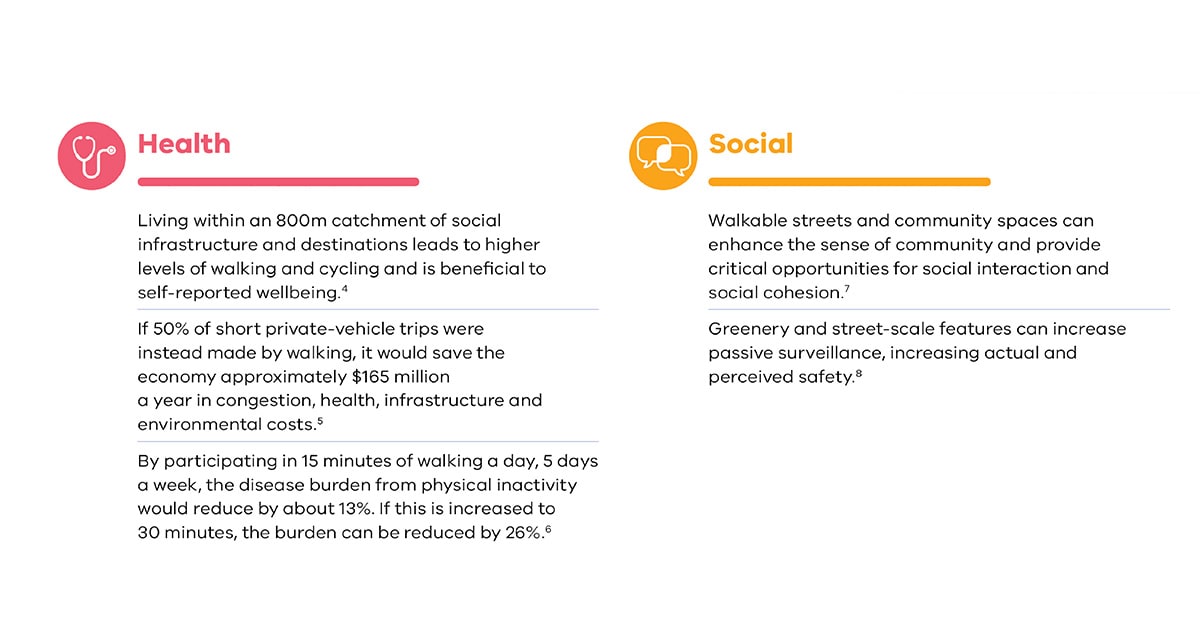

What if city residents could spend less time traveling long distances for daily practical needs, instead spending more time with family and friends, or engaging in leisure or cultural activities? That is the core idea of the 15-minute city, an urban design concept that has gained momentum over the past decade, including in some of the most prestigious developments in KSA. It focuses on creating cities where residents have access to all their daily necessities within a 15-minute walk or bike ride. This includes services such as grocery stores, schools, parks, shops, cultural attractions, and health facilities. The larger goal of the 15-minute city is to create a more livable and sustainable urban environment by reducing reliance on cars and encouraging walking, cycling and other forms of active transportation that promote health and community life.

Health, social, economic and environmental benefits of a 15-minute city (or 20-minute neighbourhoods). Diagram © State Government

of Victoria, Australia.

Despite its many potential and demonstrated benefits, the 15-minute city principle has been the subject of recent controversy in the UK. Certain commentators have speculated, without evidence, that the 15-minute city (and a closely related concept, the 20-minute neighborhood) is a plot to control people’s daily movements. However, according to 15-minute city author Natalie Whittle, the truth is much simpler. The 21st-century revival of walkable urban development, she wrote in the Financial Times, was founded on “the innate human reluctance to walk further than about a mile — or around a 15-minute journey — for routine errands.” It’s essentially about convenience and quality of life.

At the same time, Whittle says, it’s important for modern city residents to have the freedom to travel easily, whether for leisure or work. Regional and international mobility infrastructures such as rail, road, and air remain crucial, and should be conveniently accessible from pedestrian-friendly neighborhoods. “The idea that cities should connect people [to distant places] is worth incorporating into the 15-minute agenda.”

Best practices in Europe

One city that has been a leader in implementing the 15-minute city concept is Paris. In 2019, the city introduced its “Paris en Mouvement” plan, which aims to create a more active and sustainable city by 2030. As part of this plan, the city has been implementing measures to reduce car traffic in the city center, increase the number of bike lanes, and make public transportation more accessible. Paris is also adding new green spaces and investing in its public transportation system. At best, these plans ensure that essential services are easily accessible to all members of the community. To date, however, these measures only apply to the central city, not the peripheral suburbs where most of the metropolitan population lives.

Another city that has embraced the 15-minute city concept is Madrid. In 2018, the Spanish capital introduced its “Madrid Central” plan, which aims to reduce air pollution and create a more livable city by reducing car traffic in the city center. As part of this plan, the city has introduced a number of car-free zones that give more space to pedestrians and cyclists, reducing air pollution and encouraging an active street life. Madrid has also increased the number of bike lanes and improved its public transportation system.

In some communities, local agriculture and community gardening are important aspects of the 15-minute city. Modern developments in the Netherlands, for example, have been successful in providing space for urban agriculture alongside modern buildings and infrastructure. While such urban farms may not be as productive as rural farms in terms of crop output, they often become important community spaces. In providing access to fresh, seasonal produce, they also invite residents to learn more about environmental systems and provide a sense of connection to the land.

Can 15-minute cities exist in the Middle East?

Yes. Some of the world’s oldest and most beautiful cities are located in the MENA region. Those that were substantially developed prior to the middle decades of the 20th century already exhibit some of the hallmarks of the 15-minute city, based on walkable neighborhoods and local services. However, the 15-minute city concept does not attempt to turn back the clock to the days when people lacked the means to travel. Instead, it aims to resuscitate some of the benefits of classical urbanism alongside newer mobility technologies like electric and autonomous vehicles, and closely connected with public and private transportation networks. Rapidly developing cities in the Gulf region could potentially become leaders in the next wave of innovation around the 15-minute city.

Architecture and urban design are rooted in unique cultures, climates, and technologies. It’s important not to assume that something that works in one place will work in another. Yet good ideas can be adapted to suit local needs and preferences. A 15-minute city in Saudi Arabia will not look the same as one in the Netherlands—and that is for the best. The goal is not to replicate a single model across the world, but to study the best ideas and adapt or improve upon them in a contextually appropriate manner.

In KSA, a series of futuristic megaprojects show how the 15-minute city is being implemented in the Middle East. The recently announced New Murabba development in Riyadh—a vast urban nexus comprising hundreds of thousands of residential units and two million square meters of shops, cultural and tourist attractions—will bring all amenities within a 15 minute walking radius, further connected by an internal transportation system.

Additionally, Neom’s The Line appears to incorporate many elements of the 15-minute city. The planned 170km, carbon-free metropolis will have no cars, no roads and short travel times between nodes—serving as a futuristic lab for the 15-minute city in the Middle East. Amenities will be clustered around convenient nodes at short intervals, yet the entire city can be traveled end-to-end in only 20 minutes via a high-speed underground network, according to early concept plans. NEOM also includes its own agricultural production facilities.

Implementation and accessibility

To implement the concept of a 15-minute city, urban planners must consult with stakeholders and communities to consider several factors, such as the availability of land, topography, existing infrastructure, and population density. Planning for a 15-minute city should focus on creating a network of public spaces and transportation solutions that are accessible, safe, and efficient. In existing cities, this could include widening sidewalks, increasing bike lanes, and creating pedestrian-friendly streets. Additionally, urban planners should consider how to make public transportation more accessible and frequent. This could include providing more bus and train routes—as exemplified by the new Riyadh Metro system.

Accessibility is one of the most challenging and overlooked aspects of the 15-minute city. It’s essential that all members of the community have access to grocery stores, pharmacies, public services, and restaurants, as well as community amenities like green spaces.

While the 15-minute city is a relatively new concept, its principles have been time-tested over centuries. Yet in the age of the automobile, ancient wisdom on urban planning and development was lost. The challenge for urban planners and designers today—in the Middle East and beyond—is to reconcile human-scale, pedestrian-friendly development with high-tech and emerging forms of mobility.

Omrania, a renowned architecture firm, has established a reputation for excellence in blending aesthetic and functional design, setting a benchmark for architecture firms in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia