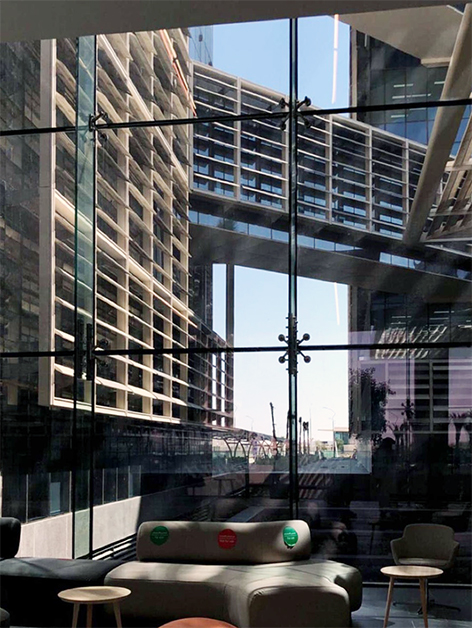

Masdar City, Abu Dhabi, UAE. Photo © Anna Ostanina / ShutterStock

Masdar City, Abu Dhabi, UAE. Photo © Anna Ostanina / ShutterStock .

In the first of our four-part series exploring Sustainable design in Saudi Arabia and the wider Middle East region, we look at the origin of the idea and how it evolved to become relevant to the unique nature of the Kingdom.

By: Marcus Leyland – Chief Architect

Almost 50 years since the 1973 oil crisis that arguably sparked worldwide interest in energy efficiency, the notion of sustainable design has evolved from a fringe cultural movement into the global mainstream of design. The ideas of energy independence and ‘off grid living’ followed an awakening amongst many as to how reliant they were on the fragility of world events. These ideas, in turn, led initially to two fundamentally different schools of thought on the notion of energy independence, energy efficiency and later the societal and economic reforms needed to bring about what later became widely known as sustainability.

Nostalgia Versus Progress

In parts of North America and Europe, one group reacted against the increasing mechanization of life and drew inspiration from a carefully edited, simplistic version of the past. They looked at how pre-industrial towns and buildings required little technology and energy in their construction and use. While much of this first school of thought was fanciful and economically impractical in any wider sense, this ‘back to nature’ approach did introduce important ideas. These included the importance of building plan form and orientation, passive energy and ventilation design, the use of new thermal dynamics from mass structures, the value of natural light and an awareness of embodied energy and recycled content in material manufacturing.

The other approach emphasized the need for better technologies to manage the environmental impact of development and construction. Following the shock of the two energy crises of 1973 and 1979, many involved in the design of buildings returned to the same approach to design as before. Some within this ‘progressive’ group saw the need to make buildings more efficient employing technological innovation. This second school of thought developed many new materials such as solar control glazing, advanced control systems for HVAC, lighting, thermal comfort, water use management, and other systems within buildings. Whilst we still take advantage of many of these technologies today, the additional cost of integrating many of these innovations into every building would prove impractical, as would the associated cost of maintenance and operations.

In the Middle East Region and most of North Africa, a debate has emerged surrounding the differences between this latest North American/European model of Sustainability, and what might be appropriate to Middle Eastern Countries. Whereas in developed Western Countries the key themes are carbon emission reduction, land scarcity, and resource efficiency, priorities in Middle Eastern Countries centered on reduction in energy consumption, a desire to demonstrate environmental stewardship, a need to enhance awareness of the unique cultural aspects of the regions architecture, and above all, a pressing need to reduce water consumption.

This debate was not new. Architects in the region had been aware for decades that much of the architecture realized during the 1970’s and 1980’s owed more to precedents in the west than any recognition or awareness of Middle Eastern Cultural traditions. The work of Hassan Fathy characterizes as early identification of this issue and demonstrates the simple yet highly effective use of ‘passive’, traditionally derived ways of controlling the microclimate within and between buildings without resorting to costly, imported technology. While proving a success in terms of recognizing the cultural traditions of the region, the design of many of these buildings resulted in unintentionally low occupant comfort levels, and a sometimes, unthinking application of traditional forms and ideas that compromised building function. The prescriptive ‘Master Architect’ approach also often did not involve other members of the design team who might have contributed to the search building efficiency in different ways.

The ‘progressive’ school of thought is exemplified by such projects as the World Trade Centre in Bahrain by Atkins Architects, and the Al-Faisaliah Tower in Riyadh by Foster and Partners. The highly advanced technology deployed in these iconic works afford excellent occupant comfort, highly energy efficient, and result in stylish eloquent architectural solutions, but at a price. Few buildings truly from this school have been completed to date, and the simple reason that much of the technology used is custom to the project and relatively costly.

The World Trade Centre in Bahrain by Atkins Architects (right), and the Al-Faisaliah Tower in Riyadh by Foster and Partners (Left)

Synthesis, or the ‘third way’

The late 1990’s and early 2000’s saw the evolution of a hybrid of the two approaches that blended the best and most economically viable solutions. Under the banner of Sustainable Architecture, this ‘third way’ has become mainstream thinking amongst the world leading architects; many of who might have previously shunned the technical and engineering aspects of their buildings for the sake of mere form. This blend of passive, traditionally inspired approaches, with carefully selected active, progressive technologies has led to some of the regions most inspiring Sustainable design to date. Projects including Fosters Masdar City in Abu Dhabi, HOK’s KAUST project in Thuwal, and Omrania’s Saudi Electric Companies new headquarters in Riyadh, all demonstrate a firm basis in tradition, with a sparing application of advanced technology and on-site renewable energy generation in ways that offer a customized approach to Sustainable design unique to the region.

Masdar City, Abu Dhabi, UAE, by Foster and Partners. Photo © Masdar

These three projects, whilst large in scale, break down their respective programs to form campus like groups of buildings, with the external envelope, and interstitial spaces within the group acting as micro-climate modifiers. Whereas at Masdar and KAUST, this is done in part actively utilizing cooling wind towers and water atomization, the SEC project uses complex layered walls and roofs, shading and landscape to temper the environment immediately adjacent to the constituent buildings. All are remarkably simple and sparing in their formal language and offer some respite from the gestured iconoclasticism of many Architectural statement buildings built in the Gulf region around the turn of the 21st century.

King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST), Thuwal, Saudi Arabia, by HOK. Photo © HOK

Whereas Masdar and KAUST were built as something of innovative demonstration projects, and as such were allocated generous budgets by their sponsors, the most recent of the three, the Saudi Electricity Companies Headquarters, was designed and built to highly commercial standards and budgetary constraints. In this sense it is a demonstration project of a different kind; one that shows that regionally relevant Sustainable Design is possible within the pragmatic commercial constraints that most developers see as fundamental to their business success.

Saudi Electricity Company (SEC) Headquarter, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, by Omrania.

The Future

It is likely that we shall see this new hybrid blend of Middle Eastern Sustainable Architectural Design evolve across all building types in the next couple of decades. As designers develop was of delivering the high-performance solutions that it aims to achieve at realistic costs, this drive for more efficient architectural solutions will provide increased value for money for owners. This approach does offer an alternative to the currently fashionable formalism that pervades the region, and perhaps the potential of a modern vernacular.

Ironically, a key driver of change and the adoption of many of these new sustainable approaches may be the rise of private finance in the development of major buildings for government and the public sector. This new procurement method requires developers to know accurately how much a building is going to cost throughout its lifespan or designed service life, to bid competitively for such work. The way this became possible was the use of life-cycle costing analysis that required complex computer software to accurately determine the precise cost of design, construction, management, operation, and maintenance of buildings.

For the first time, many of the design measures and technologies that had previously been perceived as costly add-ons during initial construction began to make sense as developers realized how much they would save across the service life of the building. For once, Sustainable design was seen by the most innovative and forward-thinking developers and owners as a commercial advantage.

Omrania, a renowned architecture firm, has established a reputation for excellence in blending aesthetic and functional design, setting a benchmark for architecture firms in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.