Co-Working Space. Photo © 4 PM production Via ShutterStock

Co-Working Space. Photo © 4 PM production Via ShutterStock .

This is part 3 of 4 in a series on the global development of office design. In the previous post we reviewed the historical evolution of regional types. In this post we explore how changing technologies have affected the design of the workplace, disrupting and reshaping spatial configurations.

By: Marcus Leyland – Chief Architect

Technology does not determine design, but it is a very important factor. The history of office and work environments ways reflects changes in the techniques of business and governmental administration, from ancient record-keeping systems to modern cloud computing.

Ancient record-keeping

Paper manufacturing and standardized scripts were the first technological determinant in the invention of the office. The first use of common spaces for the recording and transcription of the written word evolved in the Arab world following the introduction of paper-making from China in the early 9th century AD. Prior to this period, the spread of the Quran had been by word-of-mouth. With the advent of paper mills first in Baghdad, then Egypt and Palestine, the ability to record the Holy Book precisely and accurately by means of the written word became possible. The art of calligraphy was developed and standardized to represent the Arab language from its original Nabataean form in these scripts.

Originally known as Khatt, calligraphy evolved through several formal systems from its original Kufic to the cursive Nastaliq standard we know today, first used in the 14th century CE. Beginning in the 8th century CE, the Abassid caliphs, based in Baghdad, built academies and libraries where great books were translated into Arabic. This helped spawn the “Golden Age of Islam” as the religion spread across Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and southern Europe. Islamic administrative and papermaking techniques spread from Mesopotamia and Egypt west to Morocco, north to Islamic Spain, and then to the Christian kingdoms of France, England, and Germany.

Medieval scholarship

This era, known as the High Middle Ages in Europe, was the period during which the scholastic thought and study that later informed the European Renaissance evolved. Drawing on Arabic and Greek texts, and using the new technology of paper, scholars were able to develop ideas in science, philosophy, and mathematics. Prior to the European Renaissance, in Europe, the primary means of recording and archiving information was paper and ink. Spaces for the storage of scrolls, papers and bound books were conceived or chosen to minimize the risk of damage to these precious resources from sun, moisture, theft, and destruction during time of war.

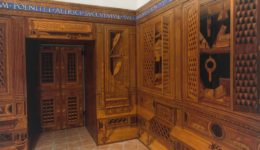

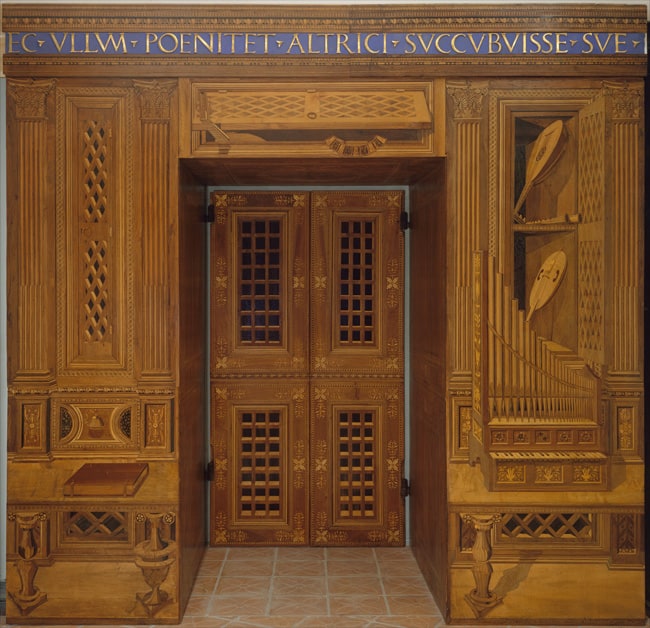

Despite the rarified work of scholars, everyday communications existed almost entirely by means of the spoken word. Rarely was a narrative regarded as important enough to be written and copied for consumption by a select few. The works of artists existed as much to record and illustrate events, and to represent ideas in both realistic and allegorical manners. Libraries were rare, and only accessible to a privileged few. In Europe, the modern notion of the office was yet to be conceived as the work of a scribe was a solitary task requiring little more than a desk in a quiet place. The equally solitary work of painters was carried out in studios or studiolos, from the Latin studere (“to study”), that were simply rooms selected for their quality of light and removal from domestic distractions.

Studiolo from the Ducal Palace in Gubbio, Italy. Photo © Public Domain

The print revolution

The invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenburg in 1445 changed the nature of written documents and widened their availability to a wider population. Printing not only allowed knowledge, opinion, and theory to be more widely circulated and stored, it accentuated a competition for ideas where not only scholars, but leaders competed for the hearts and minds of the population. The value of information and the need to control its production quickly became apparent with the clergy, the state, powerful families, and few others claiming citing their interests in their need to control information. For this purpose, libraries, archives, and the first spaces and buildings for public administration were created.

In the birthplace of the European Renaissance, Florence, Italy, the Giorgio Vasari-designed Uffizi formed the administrative hub of the City State from the early 16th century onwards. Conceived as a galleried, cellular block on four floors, it brought the form of the monastic cloister into the urban realm and integrated its functions within the complex nature of the city itself. There were no barriers and distinct boundaries between this office building and the life of the city. Staff would live, eat, and sleep within the walls of the building, and they would carry out their work away from its location if needed. The Uffizi was more a grand administrative hub, an urban condenser, than a building with fixed edges and predetermined functions.

Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy. Photo © Bridget Moyer

Renaissance administration

Parallel to the state, prominent families such as the Medici coexisted as power brokers and funders to the city—but they maintained a much more closed operation, separated by architecture from the open activity of the city. Staff operated strictly within the high stone walls of the family palazzo, or palace, such as the understated Palazzo Medici Riccardi, begun in 1444 to designs by Michelozzo. Not wanting to attract envy from rivals, Cosimo Medici the Elder rejected the earlier proposal by Brunelleschi as too decadent and ornate. Again, a cellular labyrinth of rooms linked by corridors led to large reception halls and private meeting spaces where the power trades of the day were carried out. The heavily rusticated, fortified perhaps, ground floor contained the family’s archives and offices. Clerks, bankers, and advisors worked within these highly secure areas, readily accessed by the family from the reception and dwelling levels above.

The palazzo’s elegant piano nobile, the first floor above the ground level and the most architecturally ornate, was primarily a place for meeting and impressing those from outside the family. It was intended for conversation, meetings, making deals, and plotting the downfall of enemies and competitors. When the palace was sold to the Lorena family in 1814, it was easily adapted as an ideal administration office building, a purpose that it continued to serve after it was taken over by the City of Florence in 1871. Today it serves as the seat of the Province and Prefecture of Florence. Whilst some of the original grand spaces have been restored for their aesthetic value, the building continues to serve as an effective office building, 570 years after its creation—indicating that in some respects, the requirements of office architecture have not changed so drastically after all.

And indeed, the architecture of office buildings changed little over the next several centuries in Europe. London’s East India House (1729, demolished 1861) and Somerset House emulate their Renaissance forebears not only in external expression but in their functional plan form. Perhaps because the technologies and methods of administration and commerce changed little in this period, this is hardly a surprise.

Telephones and typewriters

But big changes were coming. In 1876, Alexander Graham Bell patented the telephone after years of experimentation by many in the emerging field of telecommunications. In its earliest forms, telephones were rare within the office building and for the exclusive use of the most senior staff. It took another 25 years before telephone exchange technology was sufficiently developed to allow its use within a single office building, initially solely for communications with those outside of, or distant from the building. By the mid-20th century telephone systems became a tool for accelerating communications within a single building.

At this time, the open work offices that had developed from Taylorist principles earlier in the century, were already cluttered and noisy. Whilst the development of the mechanical typewriter into its quieter IBM Model 04 electric successor in the early 1960’s, had greatly reduced the level of noise within office spaces, they remained inhospitable, crowded spaces. As increasing postwar prosperity in North American cities drove real estate process higher, the proportion of cellular space within offices relative to open plan area became constrained further with even middle management now placed within the pool. Reactions from staff were highly negative and with the expanding market, retention of recruitment of staff became a problem for many employers.

Cubicles, computers and printers

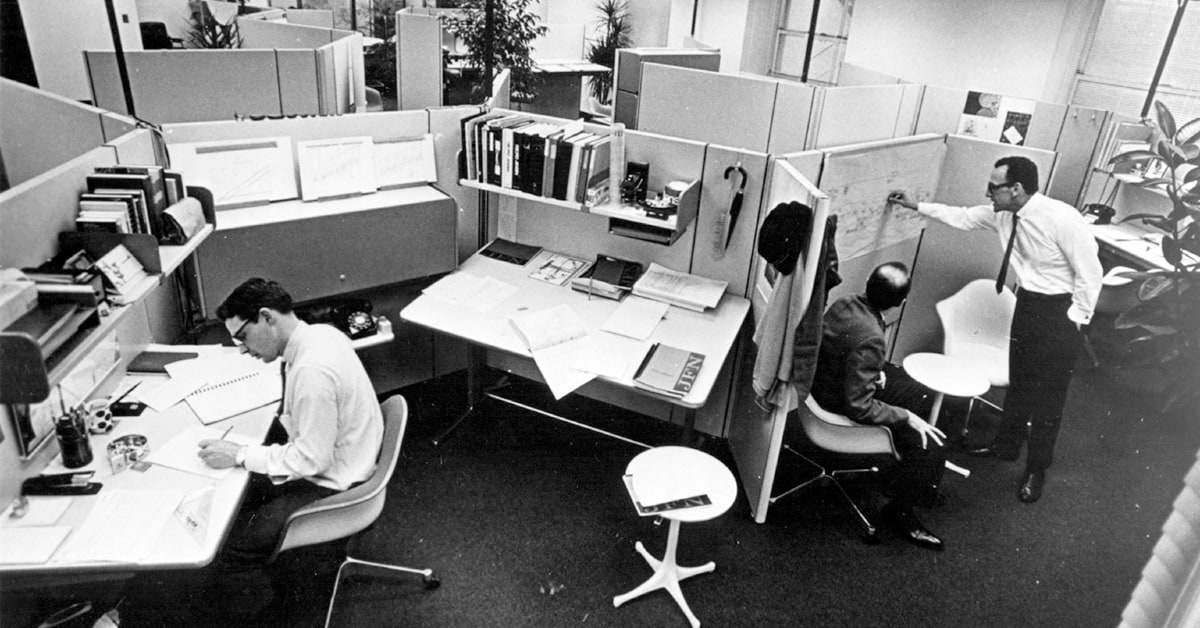

In 1964, designer Robert Propst of Herman Miller introduced the first cubicle concept to the market. This was meant to address the depersonalized nature of the vast open plan pools that characterized the modern office. They also provided a degree of spatial and acoustic privacy for the individuals within. Initially a failure due to their perceived high cost, cubicles were widely embraced only when changes in legislation intended to encourage growth allowed corporate tax write-offs against depreciated assets.

By 1968 Herman Miller’s invention, and those of lower-price competitors, began to enter the workplace in significant numbers, changing the character of the office forever. The cubicle provided the ideal environment for the introduction of the first workstation computer in the form of the Olivetti Programma 101, the later TC800 in 1974, and the first true PC, the M20 in 1982. In most buildings, cable distribution remained through ceilings, although early access flooring, first invented in 1961 for the placement of IBM mainframe computer rooms within office buildings, were adapted for use in ordinary office environments by the early 1970’s.

Herman Miller Action Office II, USA. Photo © Herman Miller

Following the addition of PCs to the office, new peripheral devices soon demanded space of their own: plotters and printers. Initially conceived as shared devices, these bulky machines required their own spaces, in effect the first cellular offices for non-human elements, to control noise and odor and to contain all the supplies necessary to their use.

New mechanical and electrical demands

The addition of this new technology to the office environment was never anticipated by mechanical and electrical engineers in the 1950s and 60s. Increased demand for cooling, electricity, and space for cabling quickly became a challenge for even recently constructed, modern office buildings. Their modest floor-to-floor story height limited the installation of additional duct and cabling capacity, and new raised floors.

By the early 1980s the problem was one of the top two concerns expressed by office tenants in the UK. Between the mid 1980s and the mid-1990s, whilst plan forms changed little, story heights increased and mechanical and electrical systems expanded dramatically. Whilst new office buildings had overcome deficiencies in capacity, they had become very expensive to operate and remained rather impersonal and unattractive spaces within which to work and do business.

A decade’s worth of experience revealed the high costs of operating these energy-inefficient buildings. Cost-in-use could no longer be ignored, and far-sighted architects and developers explored more efficient design technology. This thinking combined with the rise of the “Green” development agenda following the 1992 Conference on Environment and Development, informally known as the Rio Summit. Architects increasingly recognized the contribution of buildings to global warming and saw the twin problems of operational costs and pollution as having a single solution through “sustainable” design.

Early sustainable office design

By the turn of the 21st century, the first sustainable, commercially feasible office buildings were being realized in countries including Germany, the Netherlands, and the UK. By 2010, examples of this new architectural approach were apparent globally, the best of which were adapted to their climate and context.

Early sustainable office design addressed the building as a physical entity, and the systems within its body. Cursory attention was paid to the occupants, and in a small number of cases, early experimental models of passive ventilation and cooling resulted in uncomfortable environments that required later modification. In others, the promise of on-site renewables fell a long way short of expectations, in some cases resulting in the removal of these nascent systems. Other mistakes included the addition of well-intentioned initiatives such as car pools, vast cycle parking and experimental materials that included recycled content that gained credits under standardized models of evaluation, but with little consideration of the needs of the owners or occupants.

The headquarters for The David and Lucile Packard Foundation in Los Altos, California, USA

Mobility and personal tech

During the same period, advances in personal communications technology, in conjunction with pressures from businesses and organizations to evaluation increasing property ownership costs, resulted in a re-evaluation of how space was used within offices, and how new technologies might result in savings. The concept of Activity Based Working (ABW), first suggested in the early 1970s, was rediscovered by Erik Veldgoen in 1996. This was a two-edged approach that allowed employees a greater choice from predetermined workplace settings, and at the same time, diminishing or eliminating individual ‘ownership’ of space within the office.

A byproduct of the approach allowed businesses to reduce the unit area of space they operated for each employee, in part also by greater use of remote working. ABW evolved from the initial idea of ‘hot desking’ which simply intensified the use of a limited use of conventional workstations of cubicles by a greater number of employees by depersonalization of space only. ABW is arguably the most significant shift in office space use since the creation of the Taylorist ‘pool’ system in the early 20th century. It allows for the adaptation of work models quickly and easily within a core and shell space, and including new working models such as immersive environments, as that technology develops.

Occupant health and wellbeing

ABW had brought the individual worker back into the frame of consideration in the way the office was shaped. By 2015, it was apparent that because of the BREEAM and LEED systems, great savings were possible in the design of the body of buildings, but that occupants, as previously mentioned, felt left behind. In 2015, and initially inspired by the need to formulate a model of sustainable design for hospitals, the USGBC initiated the WELL program. WELL, administered by the International WELL Building Institute (IWBI) sought to address occupant health within the workplace. WELL is a performance-based system for measuring, certifying, and monitoring features of the built environment that impact human health and wellbeing.

As a counterpoint to ABW, which merely addressed occupant wellbeing anecdotally and superficially, WELL adopts a holistic best practice approach to physical and mental health in the workplace. It continues themes from LEED including addressing air quality management and monitoring, thermal comfort measures, and the avoidance of the use of both building and cleaning materials with harmful effects on health.

WELL introduces new measures such as potable water quality control, measures to ensure that food sole or served in the property is healthy, the use of light in a way that does not incur stress, eye strain, or illness, provisions encouraging physical health and fitness, both in building layout and fitness equipment, internal air humidity control, acoustic quality control, emergency preparedness, and measures that benefit occupant’s mental health.

Headquarter of the Saudi Electricity Company (SEC) in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Photo © Omrania

Humanizing technology in the workplace

Whilst not technologies in themselves; ABW and WELL do bring the fundamental technology of the workplace back to the forefront in shaping the office, namely the human occupant. For 150 years, human workers themselves have been forced to adapt to changes driven by their tools, finally in the early 21st century, ABW and WELL have made the human condition the key technological determinant of the office environment.

This combination of ABW with WELL represents the current state of the art in office design. No doubt this new frontier will continue to evolve and the three key determinants of office design; the market, work technology and social demands themselves continue to evolve. The only certainty in the future of the office is change itself.

As an architecture and engineering firm, Omrania stands at the forefront of innovation, making a significant impact among architecture firms in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, with its sustainable and forward-thinking designs.