A masterpiece of Moorish architecture in the historic quarter of Fez, Morocco, the Al-Qaraouiyine Mosque was rehabilitated 2004–2007 by a team lead by architect Mohammed Fikri Benabdallah. Photo © saiko3p.

A masterpiece of Moorish architecture in the historic quarter of Fez, Morocco, the Al-Qaraouiyine Mosque was rehabilitated 2004–2007 by a team lead by architect Mohammed Fikri Benabdallah. Photo © saiko3p.

Historic mosques pose unique challenges for restoration and preservation. While it is important to preserve the building fabric itself, it is equally important to respect the historic evolution of mosque forms over time, and to consider the role of social and urban context.

By: Nihad Alamiri – Marketing Manager. May 2017

For much of the history of Islam, renovations of mosques reflected evolving needs, with less attention to the potential value of conserving older layers. Most historically significant mosques have witnessed multiple transformations over the centuries, with each addition or renovation typically carried out in the style of the given period. Restoring a mosque therefore requires elaborate documentation of all the layers of history embedded in its architecture, some of which are manifest, others of which may have been lost from view.

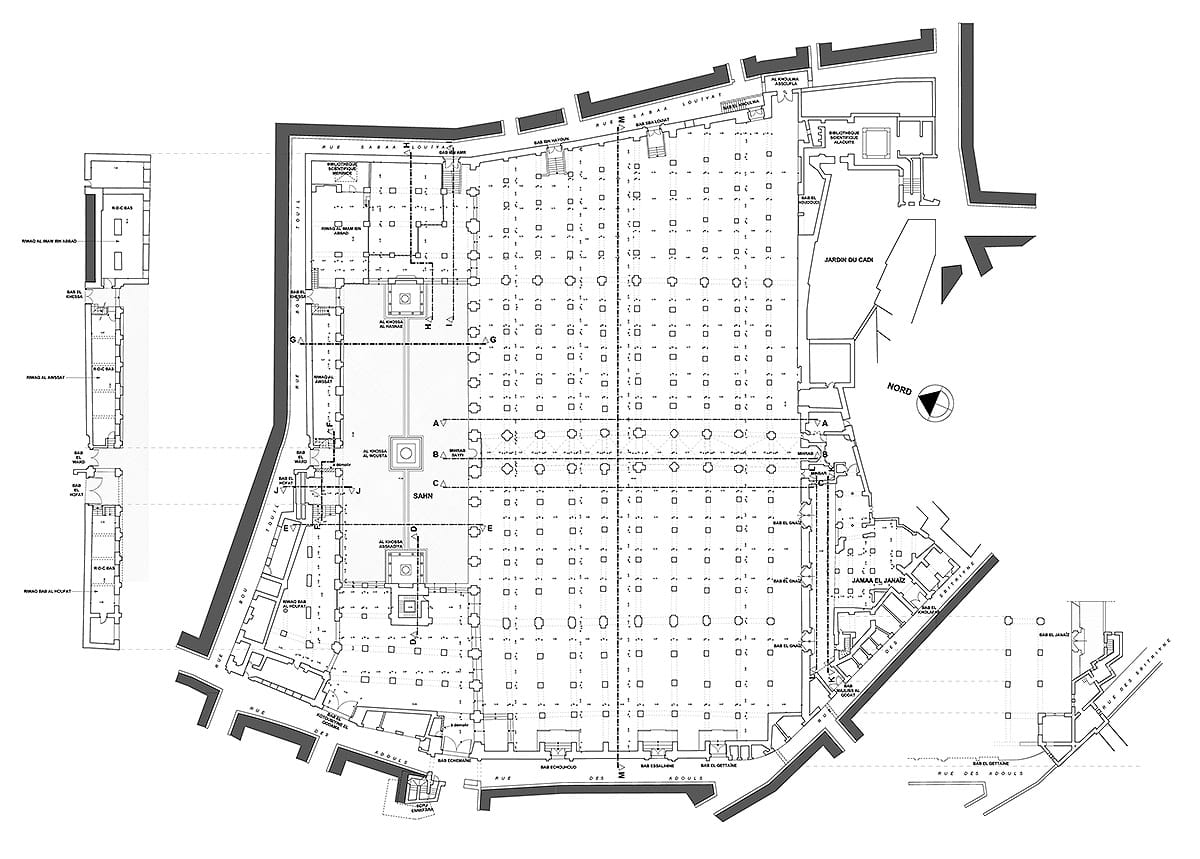

Further complicating the matter is the fact that, as noted in our previous post, many historic mosques evolved to accommodate various types of use — including educational, civic, ceremonial, celebratory, and social activities — in addition to their primary role as a place for prayer. One such example is the Al-Qaraouiyine Mosque in the historic quarter of Fez, Morocco, part of an active university and UNESCO World Heritage site that has developed over the course of a millennium. The mosque itself was carefully rehabilitated 2004-2007 by a team led by architect Mohammed Fikri Benabdallah, earning a place on the shortlist for the Aga Khan Award, which praised the effort “not only to preserve the historic fabric of the mosque but also to revive its cultural and social role in the life of the citizens of Fez and to enhance its use as a place of worship and a place of learning.”

This holistic approach to restoration improves upon early mosque restoration efforts in the Middle East, which tended to treat the mosque as an architectural object, separate from its historic context. The result was that modern streets and avenues were introduced immediately adjacent historic structures, obscuring the organic relationship between the mosque and the surrounding urban fabric. Today, however, as architectural heritage practices continue to evolve, there is a heightened sensitivity to conservation and the need to respect all historic periods.

Additional recent examples of successful mosque restoration and preservation work can be seen in Bosnia and Herzegovina, where five monumental mosques have been restored since 1999, in the wake of the war. According to the Islamic cultural research organization IRCICA, the restoration of these mosques “is closely connected with the historical, cultural and social environments attached to each site and structure.”

As these examples show, the value of mosque restoration and preservation efforts lies not only in the material and spatial aspect of the prayer hall, but also in their continuing vitality as community gathering places, hosting a multitude of functions. This combination is what allowed these mosques for many centuries to serve as civic centers for a busy urban milieu. Fortunately, states have begun to establish conservation programs not only for mosques, but also for the historic neighborhoods around them, and for the revitalization of traditional crafts needed to maintain the building materials and ornamental details.

A mosque without a living connection to its community is only an artifact. What makes a mosque such an important and dynamic space is that it brings all the complexity of its production, use, and maintenance into a living space.

In a future post in this series, we will review several architectural strategies for designing new mosques today.