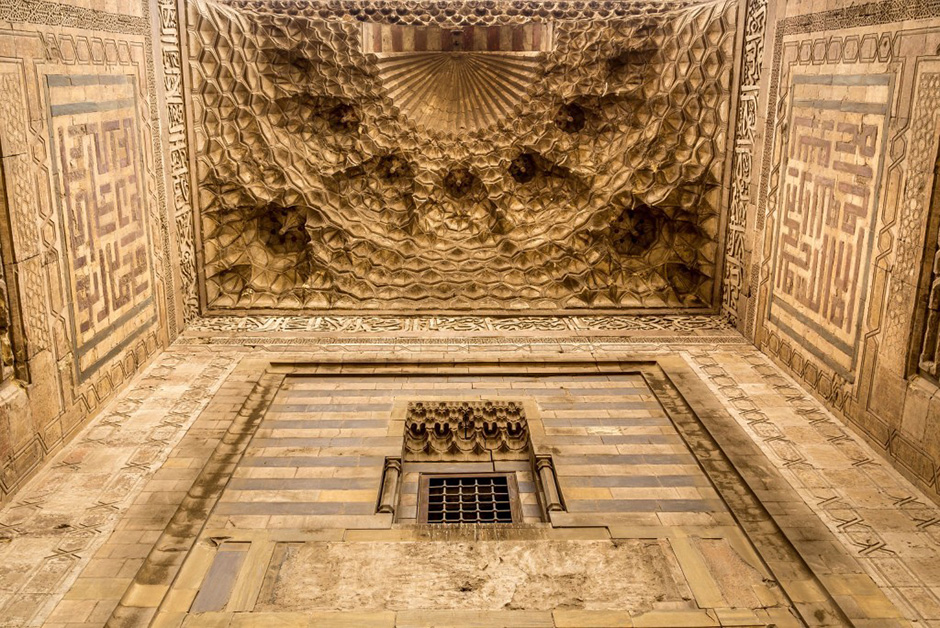

Detail of the Al-Tawashi Mosque, Aleppo, Syria. Built 1348 (Mamluk era), renovated 1537. Muqarnas above the main gate. Photo © Daniel Demeter

Detail of the Al-Tawashi Mosque, Aleppo, Syria. Built 1348 (Mamluk era), renovated 1537. Muqarnas above the main gate. Photo © Daniel Demeter

The muqarnas, rooted in function, became a powerful sculptural element in Islamic architecture, yielding beautifully intricate compositions of solid and void. Ancient and medieval craftsmen learned to achieve breathtaking results by applying three-dimensional geometric patterns to the underside of domes, half-domes, and vaults.

At first glance, it seems that the muqarnas could almost be the result of natural forces. Its organic structure is reminiscent of stalactite-covered ceilings of caves, enormous crystal formations, or even the honeycomb cavities of beehives. It is, of course, a product of human creation, and an inspired one at that. Based on geometric abstraction and repetition, its seemingly organic aspect gives an important clue to its gradual historical development through an evolutionary process of innovation and variation.

Muqarnas are known for their decorative effects, but they were developed from the 10th century CE to serve a specific architectural function related to dome and vault construction. The muqarnas is a subdivision and refinement of the basic corbeled squinch, a wood or stone element that serves as a transition from rectangular walls to a circular dome, popularized during the Fatimid dynasty in North Africa and parts of the Middle East. Squinches work by filling in the upper corners of a square space to form an octagon or eight-pointed star, which is a more advantageous form on which to construct and support a dome.

While the basic squinch did its job well enough, Islamic architects and engineers looked for ways to improve and embellish it. Domes began to soar higher and higher, necessitating a composition of joined squinches for structural support. These three-dimensional composite patterns utilized the same ingenious geometry as the two-dimensional tessellations designed for tiles and screens, bringing art and architecture together. As a result of this basis in geometric tessellation, the cellular pattern of muqarnas is infinitely scalable, which builders exploited to create increasingly large and impressive compositions. Muqarnas remained in use all over the Islamic world even when they eventually became obsolete as structural elements, thanks in part to their beauty and exceptionally flexible design.

Related: How Geometry Is Used in Islamic Design

But how are these complex structures even built? The answer to this question is found in the incredible world of Islamic geometric design. Because squinches form an eight-pointed star, a tessellation pattern with four-fold symmetry is a natural fit. This is what the simple square-style muqarnas plan looks like. The process of designing a muqarnas begins with a drawing of a two-dimensional tessellation with concentric rings. A muqarnas is composed of several interlocking layers stacked on top of each other, and these rings denote the different layers that will be in the three-dimensional structure. The four-fold tessellation can be broken down into different types of shape. Each type refers to a particular sculptural element that ultimately fits together to form a cohesive muqarnas structure.

More complicated muqarnas utilize more complex tessellations with five-fold, six-fold, seven-fold, or greater symmetry. As complexity of the tessellation increases, so does the number of different sculptural elements. These stunning works are masterfully planned to fit together with mathematical precision.

Historically, the construction of the muqarnas’ cellular components grew increasingly efficient with improved fabrication technologies. Older muqarnas were made with hand-carved modules from solid blocks of stone, brick, or wood. As their structural importance decreased and complexity increased, these modules began to be constructed with plaster casts mounted on wooden frames, allowing for precise construction that was cheaper and faster. Modules could be composed of flat or curved surfaces and arranged in an infinite variety of patterns. They were also often decorated with carved or tiled patterns to make them even more awe-inspiring.

The muqarnas is a triumph of Islamic geometry and design, and can be found in most parts of the Islamic world. This incredible element took full advantage of the most sophisticated mathematics and engineering to create a masterpiece of architectural decoration that continues to baffle and inspire onlookers to this day.